The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) made a huge blunder yesterday. It accidentally posted Chairman Gary Gensler’s draft speech online, complete with internal edits and suggestions.

This draft was meant for the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Folks quickly archived the speech before it was removed.

The speech focused on the “public good of disclosure,” but the real irony here is that the SEC disclosed something it really shouldn’t have. The document showed a behind-the-scenes look at how Gary’s speech was crafted.

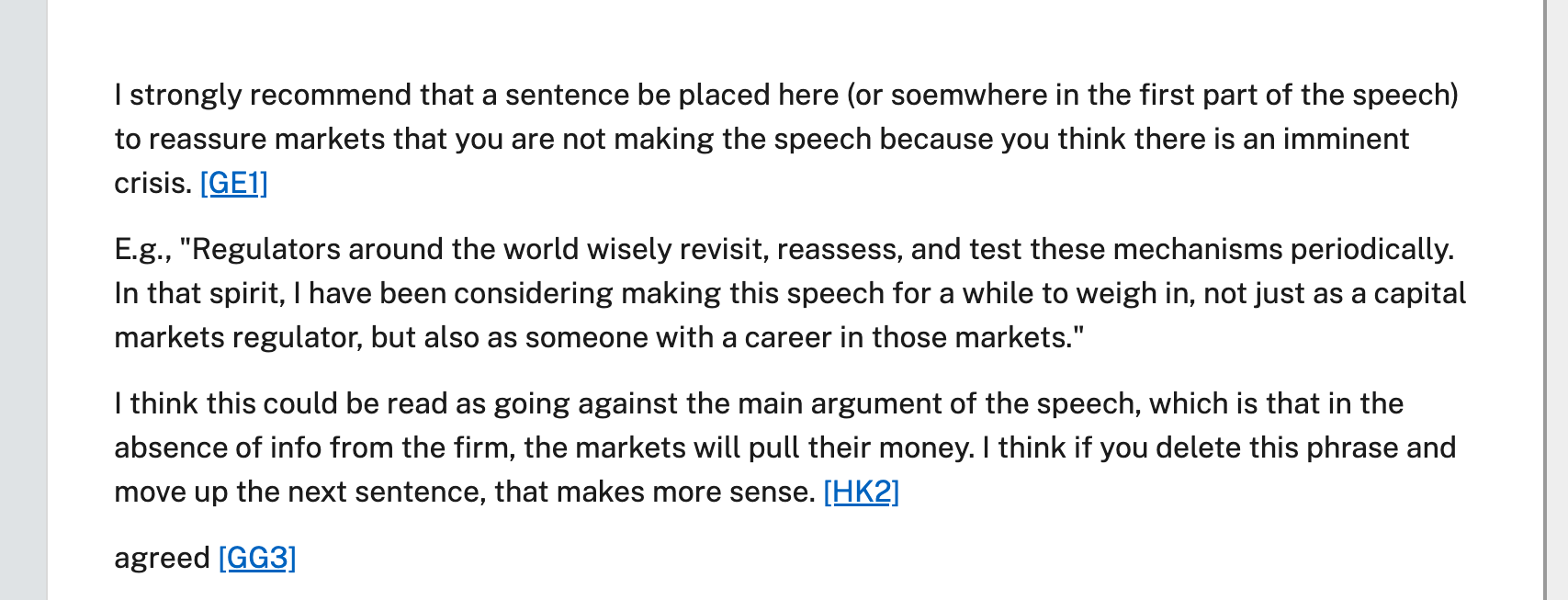

There were plenty of internal comments from SEC staff, pointing out repetitive statements, “diplomatically helpful” tweaks, and suggested cuts to trim the fat.

Key points in Gary’s speech

Gary’s speech started with a quote from Adam Smith in his work, “Wealth of Nations” about the public benefits when information is free. It’s the same concept we all know: markets work better when everyone has access to good, reliable data.

Gary tied this to the idea of disclosure, saying that no one private company will invest enough in creating this type of data for the public good.

He referenced Franklin Roosevelt and how U.S. securities laws were designed to ensure that investors could take risks but only if companies gave “complete and truthful disclosure.”

The SEC chair also brought up a paper from George Akerlof about how markets price goods with uncertain quality, using the example of used cars.

This analogy led to the point that without reliable disclosure, markets collapse. That was the key argument. When companies fail to disclose properly, it screws up the market for everyone.

Gary threw in a personal story about his father’s small business in Baltimore, pointing out that no one bailed him out when he couldn’t meet payroll. He extended this to say that businesses (big or small) shouldn’t expect rescue.

They need to operate responsibly, allocate capital efficiently, and avoid taking excessive risks. This was Gary’s segue into discussing financial system risks.

History is full of instances where failures in one corner of the financial system spilled over and hurt families, investors, and businesses.

Gary mentioned the safeguards in place since the 2008 financial crisis, including “loss-absorbing capital” for big institutions. The idea is to have investors take the hit when a company collapses, not the public.

Who needs disclosure?

Gary’s speech laid out exactly who needs this disclosure. Securities holders, counterparties, and depositors. Whether it’s debt holders, swap counterparties, or uninsured depositors, they all need clear, reliable information.

He drove home the point that in times of crisis, disclosure is the only thing that can prevent a market from completely unraveling.

Gary got personal again, recalling his time at Goldman Sachs during the collapse of Barings Bank in 1995. When things got bad, he made sure no money or securities left Goldman for Barings.

Why? Because without proper disclosures, it was too risky. That was his lesson for today’s institutions. If things go south, and you don’t disclose, people will pull their money. It’s simple risk management.

Gary said the disclosures need to be ready by the time markets open in Asia after a restructuring, which typically means Sunday night in Europe and the U.S.

Throughout his speech, Gary mentioned how the SEC collaborates with global regulators. He shared that the SEC’s discussions with agencies like the Bank of England have been productive.

These international dialogues are meant to ensure that global financial institutions comply with U.S. securities laws, especially during a crisis.